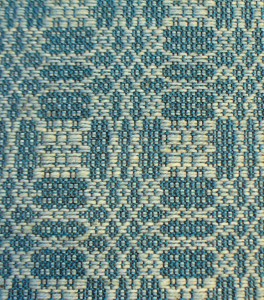

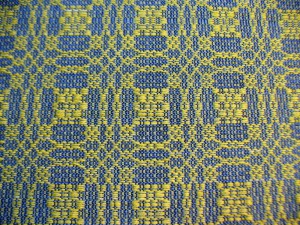

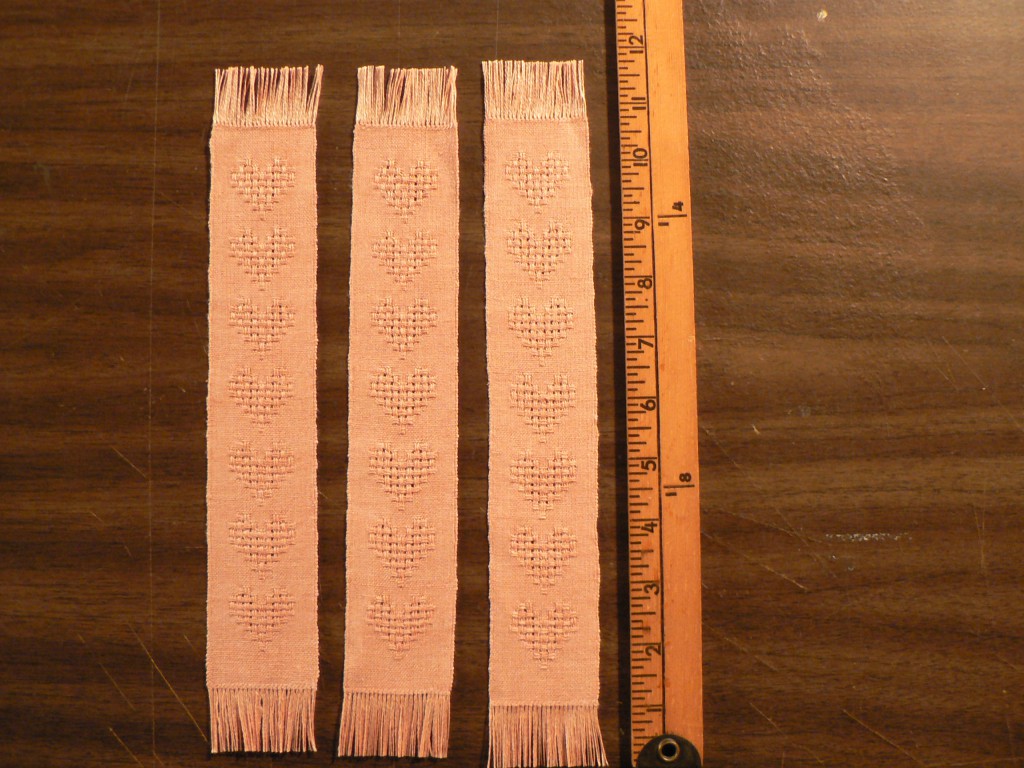

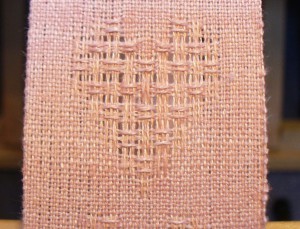

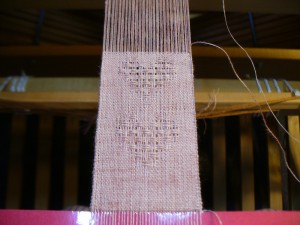

Since my madder-dyed linen heart-motif Huck lace bookmarks have been selling pretty well, and since Mothers Day is coming up soon, I decided to weave some more of them. Also, I thought my loyal readers might like a little break from photos of small flax green plants (as there will be a lot more on the way). So, here’s a photo of a bookmark in progress, showing the edge of the two-inch spacer I use to separate each one.

There are a lot of steps involved in planning and weaving anything. There are more steps involved if you dye your own yarn and, like me, do not necessarily dye it for a specific project. For example, I had dyed three skeins of 40/2 linen with madder a while back, and had used two of them for my previous batch of bookmarks. Luckily, I keep copious records and I always “show my work,” since I was raised in that 1980s math-generation. So, I knew that I had used 2.16 ounces for the warp last time (with a little left over) and 1.56 ounces for the weft (with almost a full bobbin left over). With 3.72 ounces I wound a ten yard warp and wove 23 bookmarks, plus some weft to spare.

There are a lot of steps involved in planning and weaving anything. There are more steps involved if you dye your own yarn and, like me, do not necessarily dye it for a specific project. For example, I had dyed three skeins of 40/2 linen with madder a while back, and had used two of them for my previous batch of bookmarks. Luckily, I keep copious records and I always “show my work,” since I was raised in that 1980s math-generation. So, I knew that I had used 2.16 ounces for the warp last time (with a little left over) and 1.56 ounces for the weft (with almost a full bobbin left over). With 3.72 ounces I wound a ten yard warp and wove 23 bookmarks, plus some weft to spare.

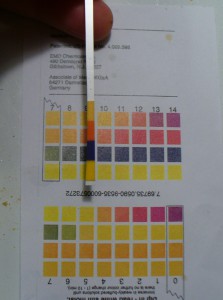

My third skein was 1.7 ounces, a very pale but pretty shade of bluish-pink (the others were more on the red/orange/salmon side of pink). That’s about half as much as I used in my last project, and the question was, how many bookmarks could that make? There are a few ways to find out. Here’s my way.

Yarn is usually sold with a certain amount of helpful information provided, e.g., its size and ply. Sometimes the vendor will also give you a measurement called “yards per pound” which tells you just what it sounds like: how many yards of that yarn it takes to weigh a pound (or an ounce, if you divide by 16). If you don’t know the yards per pound, you can figure it out (or get a good approximation) using a nifty tool called a McMorran yarn balance. You could use the yards per pound for the yarn, and the weight of your skein, to figure out how many yards your skein is.

However, when dealing with limited quantities of naturally dyed yarns (or handspun, naturally dyed yarn, even more so), I have found that the best way to be certain of what I have is to measure. Ideally I would have a niddy noddy that measured skeins by the yard or some other useful increment, but mine doesn’t. So, I often count out the length on a warping board, and that’s what I did this time. OK, done! I had 630 yards of pale pink. Since I had roughly half as much yarn as I used in the last batch, I estimated that I could wind a 5 yard warp and get about 11 bookmarks out of it. But how to be certain? (Certainty is important to me, to a point). Math to the rescue.

To calculate the amount of yarn I’d need for the warp, I first multiplied the width in the reed by the ends per inch (which really just tells you the number of ends in my project, which I actually knew already). My project has 75 ends (a bit more than 2 inches in the reed sett at 36 ends per inch, or epi). Then, I multiplied that by the number of yards in my desired warp, which means I’d need 375 yards for a 5 yard warp. To calculate the number of yards I’d need for the weft, I multiplied the length of each bookmark (12 inches) by the number of bookmarks I thought I could make (11), which meant I would need to weave 132 inches of warp. That’s the length part of the bookmark (two inches of each bookmark is just fringe, which doesn’t use any weft, so I figure this covers the take-up and then some…see below). Now for the width, 75 ends, which means I need a total of 9900 inches (75×132) or 275 yards of weft (divide 9900 by 36). Add that to the warp requirements, and you get 650 yards total. Well, I was 20 yards short, but luckily I had a bobbinful from last time that was definitely more than 20 yards.

My way is sort of a middle way. I could have gone with my initial estimate, which was accurate enough. Or, I could do a lot more fastidious calculations involving additional factors, including draw-in (how much the project pulls in as you weave compared to its width in the reed), take-up (how much it shortens in length due to the fact that the threads are traveling over and under one another; even though the distance taken up by each little bump is minute, it adds up over the length of the warp), and shrinkage (how much it shrinks when you wash it). I have notes about all these things from the last batch of bookmarks (“I have detailed files…“), but I glossed these considerations because eventually you just have to get started on the weaving before it actually IS Mothers Day.

So, I wound a 5 yard warp, dressed the loom, and began weaving away. The first two bookmarks were happy enough (the second was a little squat from beating too hard). Then near the end of the third, I got one broken end, and then immediately another. Grrr. Broken ends are when one, or more, of the yarns in the warp break. Then you have to stop and fix them, and it slows everything down. These bookmarks take me about an hour and a half *each* as it is (including winding the warp, dressing the loom, weaving, washing, ironing, trimming, but not including the dyeing because that labor is infinite and cannot even be quantified). So, I fixed them and then decided I needed to be more strategic about preventing any more broken ends.

A note here. I had problems with broken ends last time, too, and didn’t ever solve the problem. I blamed my yarn, and thought perhaps it was not high-quality. But then I had the good fortune to confer with another weaver who weaves with the same yarn, and he said he has no trouble with it and thinks it’s very good quality. He also hand-dyes his own yarns, but with synthetic dyes, so they are not subjected to the same high-temperature, high-alkaline treatment that mine are. The fault, we decided, was in my comparatively harsh treatment of the fibers in the scouring process (too much soda ash and boiling water is maybe a bad thing). Something to keep in mind as I perfect my cellulose techniques. In sum:

1. There was nothing intrinsically wrong with the yarn.

2. I only had myself to blame for its weakness.

3. I will certainly need to continue to use soda ash and may run into this problem again.

Thus, I’d better find a way to solve the problem.

Much of the information I have read about weaving with linen insists that you have to size the warp (or apply “paste”). I have never sized a warp. I admit my total ignorance, and even prejudice, on this matter. Partly, I just can’t believe it actually helps rather than make everything worse, though I don’t want to offend the hundreds of weavers who say it does help. But mostly I cannot imagine having a lot of sticky-when-wet-dusty-when-dry starch smearing all over my lovely loom and getting everything gross. NO!

So, instead I cast about in my memory for other ideas I had read about…. Linen fibers are stronger when damp. Weave in the basement? Don’t have one. Run a humidifier by the loom? Our apartment is built on a concrete slab by a stream in the floodplain of the Fort River, more generally located in the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts, on the east coast of the United States of America. I can’t imagine voluntarily adding extra moisture to the air. We have to run a dehumidifier in the summer to keep the mildew at bay. So, NO! Then I recalled someone saying that it used to be her job to spray the warp to keep it damp as her mother worked. So, I acquired a clean spray bottle (ours always get filled up with fish emulsion or borax or vinegar or somesuch thing, don’t ask me why).

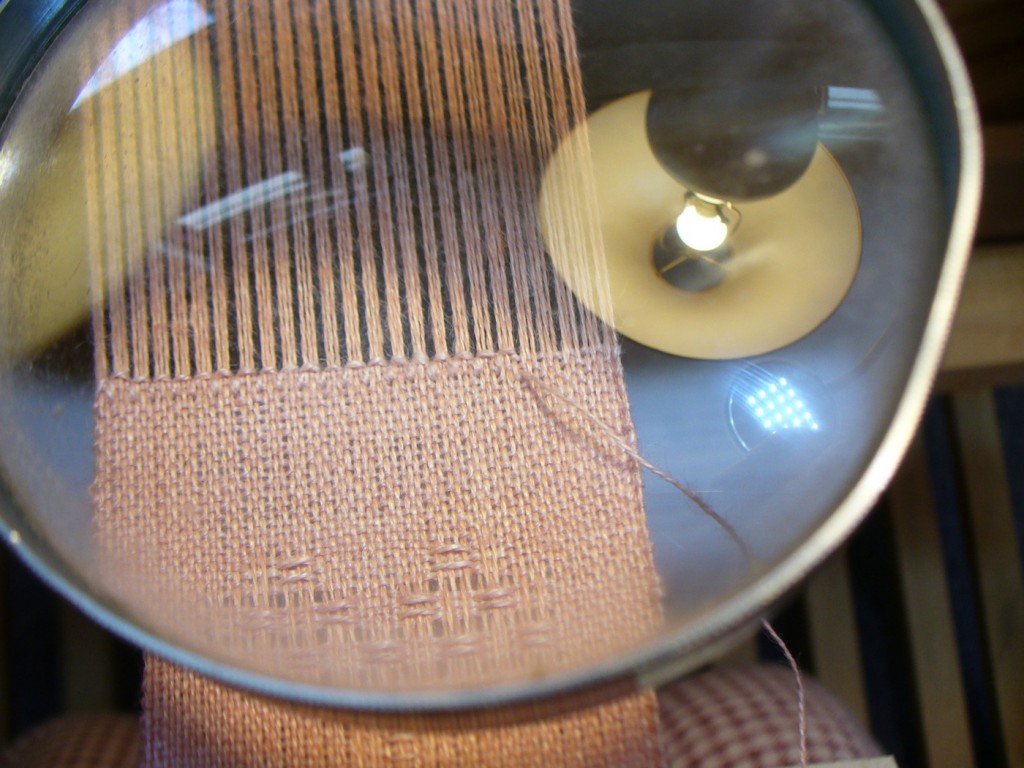

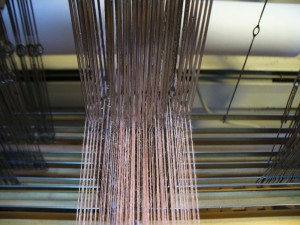

I put some water in it, and I sprayed the warp just at and above the fell line (where the beater presses the new rows, or picks, of weft into place). Bad idea. Everything got wobbly, the fibers swelled up, nobody could stay in their correct place and threads were pushing and pulling all over the place. It was a sad sight to see among my orderly little linen threads. So I let it dry. Then I decided to spray up where the beater rests when it’s upright (the white cloth in the photo is to absorb excess water and wipe off droplets from the shuttle race and reed).

I put some water in it, and I sprayed the warp just at and above the fell line (where the beater presses the new rows, or picks, of weft into place). Bad idea. Everything got wobbly, the fibers swelled up, nobody could stay in their correct place and threads were pushing and pulling all over the place. It was a sad sight to see among my orderly little linen threads. So I let it dry. Then I decided to spray up where the beater rests when it’s upright (the white cloth in the photo is to absorb excess water and wipe off droplets from the shuttle race and reed).

Then I pulled the beater forward and sprayed in amongst the heddles.

Then I pulled the beater forward and sprayed in amongst the heddles.

This was the zone of weakness, where the breakages occurred, where there must have been a bad combination of abrasion and stress. In addition to keeping that region of the warp damp, I also kept the fell line closer to the breast beam and advanced the warp more often so I was always weaving with the widest possible shed. These techniques are good practice anyway, but when I’m feeling pressed for time I try to push it a little. You can’t really push linen. I re-sprayed each time I advanced the warp. And ta da! Success! I wove 5 more bookmarks with narry a broken end!

This was the zone of weakness, where the breakages occurred, where there must have been a bad combination of abrasion and stress. In addition to keeping that region of the warp damp, I also kept the fell line closer to the breast beam and advanced the warp more often so I was always weaving with the widest possible shed. These techniques are good practice anyway, but when I’m feeling pressed for time I try to push it a little. You can’t really push linen. I re-sprayed each time I advanced the warp. And ta da! Success! I wove 5 more bookmarks with narry a broken end!

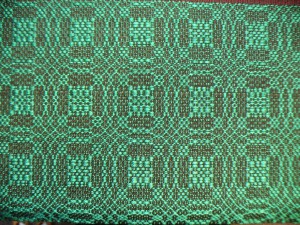

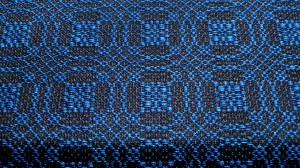

Last but not least, if you read my earlier post about hemstitching and Chuang Tzu, you may remember my trouble with fraying in the hemstitching process. I tried adding twist as I worked, using a magnifying glass, and other tricks. But the one that really seems to work is wetting the thread. Don’t get it too wet, or it swells up, and then the water absorbs into the woven cloth and it also swells up, and then even with a magnifying glass you can’t see where the holes are or get your needle through…. Enough water to make it damp. Once in a workshop at Long Ridge Farm, when she was describing how wet you want your cloth when you apply soybean-milk as a binder, Michele Wipplinger described it as feeling damp, but only just damp, not wet, and primarily cold. You feel for the temperature. It’s a bit like that with the hemstitching thread (which is a piece of extra weft yarn reserved for the purpose of securing the edges of my bookmarks. Six times the width of the bookmark is optimal. Five times is enough, but it cuts it a little close and is stressful.) You want it cool, damp, but not dripping wet. And bingo.

You can go buy my new batch of bookmarks at the Shelburne Arts Co-op in Shelburne Falls or at Saw Mill River Arts in Montague.