I know that I ended my last two posts by saying that my “next” post would be about goddesses, carts, and plowing and/or Plough Day. Instead I continued to write about spinning prohibitions and the goddesses/folklore figures who imposed them. Well, this post isn’t about Plough Day, either. Sorry about that. I will get to it eventually. Very soon. I promise.

I know that I ended my last two posts by saying that my “next” post would be about goddesses, carts, and plowing and/or Plough Day. Instead I continued to write about spinning prohibitions and the goddesses/folklore figures who imposed them. Well, this post isn’t about Plough Day, either. Sorry about that. I will get to it eventually. Very soon. I promise.

Meanwhile, I have been doing more reading and thinking on the topic of why and when people may have engaged in or avoided certain tasks (spinning, weaving, plowing), and the festivals or traditions that demarcate the appropriate times for these labors. I’m still just talking about Europe, here.

Just as there were prohibitions against performing certain textile-related tasks on certain days, there were also days on which it was considered advantageous to begin or perform certain tasks. In the Carmina Gadelica I came across a footnote that mentions that “setting” the warp was done on a Thursday in Scotland.

I am not sure whether “setting” includes both winding the warp and dressing the loom or just winding the warp. I suspect it involves both tasks, since the note describes how the housewife and her maidens would get up early to “put the thread in order.” This sounds like threading and sleying as well as warping, to me. The reason given for Thursday being such a good day for “setting” the warp is that Thursday is the day of St. Columba.

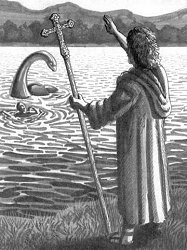

St. Columba is a major figure in the transmission of Celtic Christianity from Ireland to Scotland in 500s. He’s not a patron saint of weaving in particular, but he is called on to assist with a very wide range of tasks (including scaring off Nessie). I will not go into any of the literary, political, or other fascinating aspects of hagiography here, but I get the sense that Columba took on some of the super-human powers of the pagan figures he displaced by his zealous missionary efforts on behalf of Christianity.

St. Columba is a major figure in the transmission of Celtic Christianity from Ireland to Scotland in 500s. He’s not a patron saint of weaving in particular, but he is called on to assist with a very wide range of tasks (including scaring off Nessie). I will not go into any of the literary, political, or other fascinating aspects of hagiography here, but I get the sense that Columba took on some of the super-human powers of the pagan figures he displaced by his zealous missionary efforts on behalf of Christianity.

The next footnote states, “In Uist, when the woman stops weaving on Saturday night, she carefully ties up her loom and suspends the cross or crucifix above the sleay. This is for the purpose of keeping away the banshee, the peallan, and all evil spirits and malign influences from disarranging the thread and the loom. And all this is done with loving care and in good faith, and in prayer and purity of heart.”

So, you’d start weaving on Thursday, an auspicious day, then take a break for the sabbath. Nevertheless, even when you have a legitimate reason to take a break from your labors, you still have to take precautions. You’re not a slacker. You work hard. You’re careful and responsible. You want to make sure that nothing messes with your warp (or the flax on your distaff) while you’re attending to other responsibilities.

It makes sense to me that people would have reasons and traditions regarding when to work and when to rest, and how to mark the transition between the two. But the need to protect your work while you’re away raises the question of who might have been messing with your warp (or flax) and why. Who was helping you and who was your adversary? It’s hard to tell. Lots of mysterious things can come along and create chaos. The cat. A brownie. A toddler. Frau Holda. Some drunken ploughboys.

On any given day of the week, did you have to convince Holda or Perchta, or the local equivalent, that you weren’t shirking your weaving or spinning responsibilities when you did other equally essential things? If so, it must be nice to have a day or night when you could legitimately take a break. If you’re worried about offending Frigg then don’t spin on a Thursday, but maybe it’s a good day to weave if Columba’s got your back. Once you became a Christian, did you have to convince these same entities not to be double-mad with you? “What?! You’re not working? You’re not working because of that new guy?” Poof, your flax goes up in smoke, or your warp gets snarled. I’m speculating, but you can see the human conundrum. Gods! Can’t spin with em’, can’t weave without ’em.