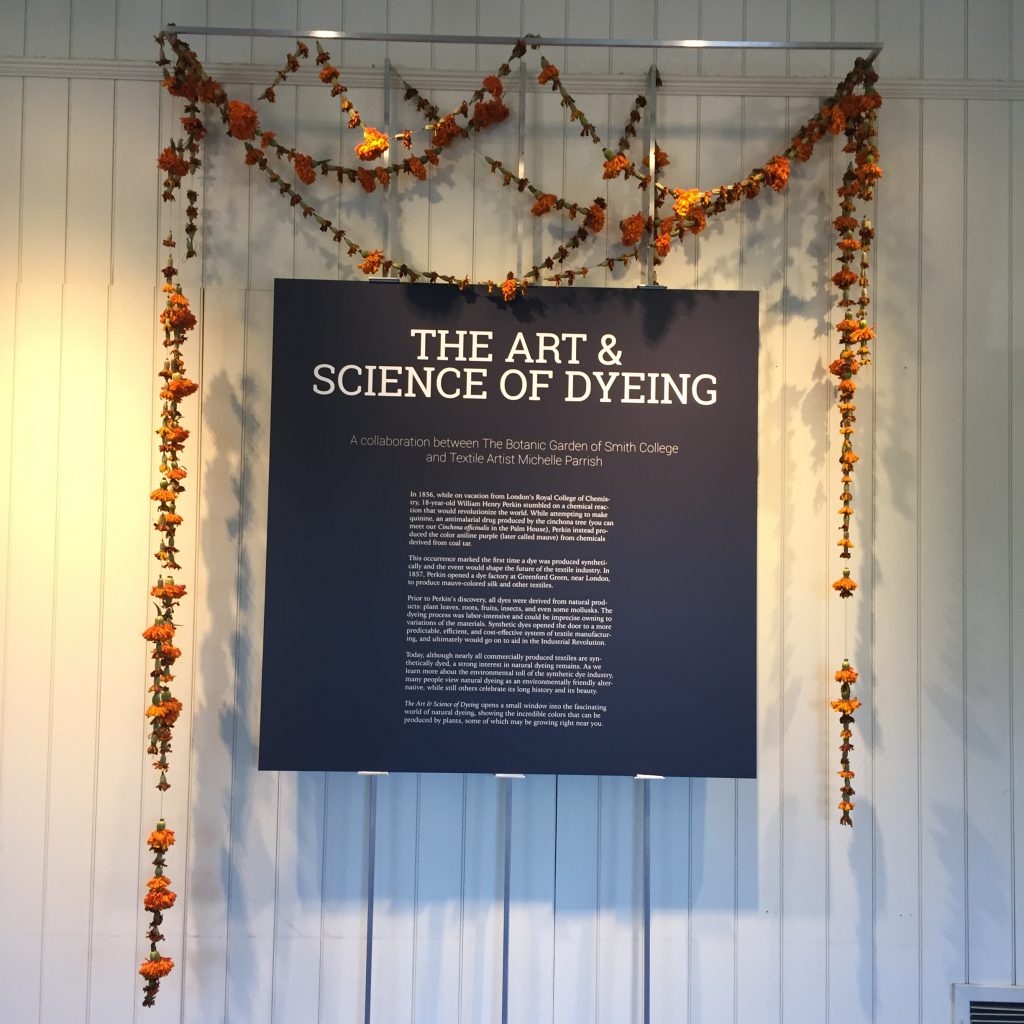

During the week that I ran the bolted woad vat in July, I also ran weld and madder baths. This post is about the madder baths. All of the dyeing I did that week was for the Art and Science of Dyeing at the Botanic Garden of Smith College. (12/31/2023 Thanks to the Wayback Machine for the link to the old Botanic Garden site!)

I was planning several consecutive days of dyeing, so there was a lot to keep track of. Here I was on Tuesday night making a game plan for what had to happen when, and doing a lot of math regarding measurements and quantities:

Part of what was tricky was that I was dyeing two different fibers, silk and linen, which need different preparations. I was also running that woad vat, and the weld baths. We were aiming to dye lengths of cloth in shades of blue, red, orange, and green that week. The quantities were large, at least compared to my usual projects, and we were trying to photo-document everything and coordinate our schedules. Many logistics.

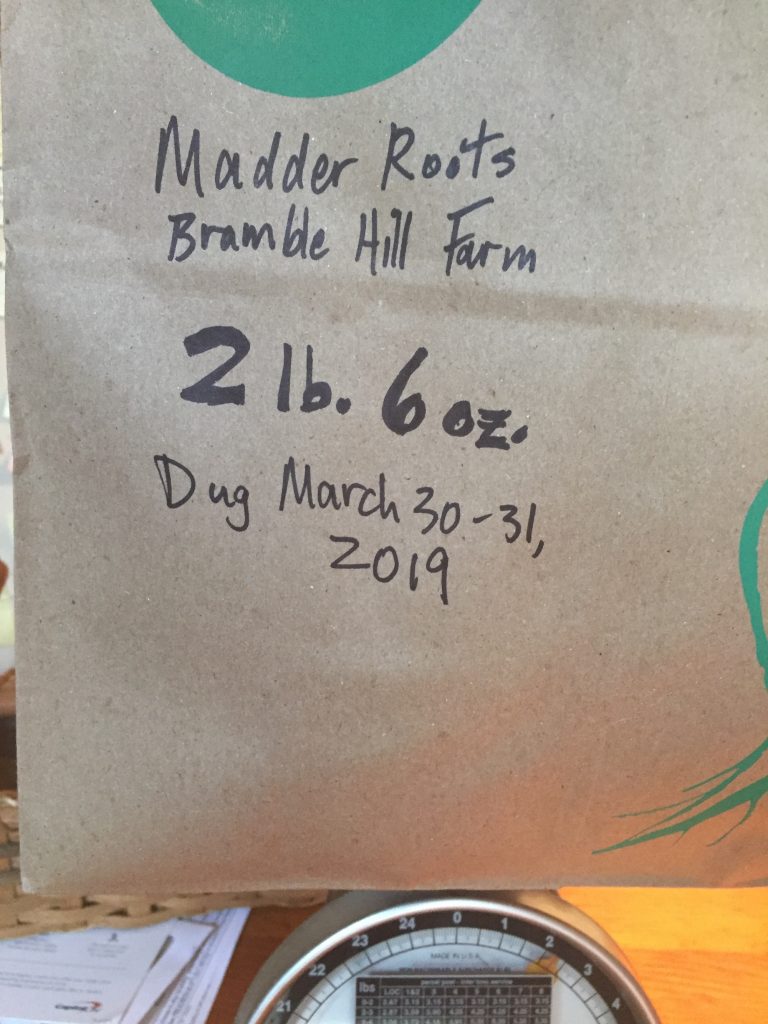

We measured out the madder and weld on the same day that we ran the woad vat, Wednesday July 10th. I wanted rich colors, so we measured the dyestuff based on 100% of the weight of the goods. The cloth that we were planning to dye weighed 51 ounces. We used the same quantity of plant material so we had a 1-1 ratio of plant material to fiber. Each piece of cloth was 16 inches wide and 9 feet long, so it was pretty heavy (the linen in particular).

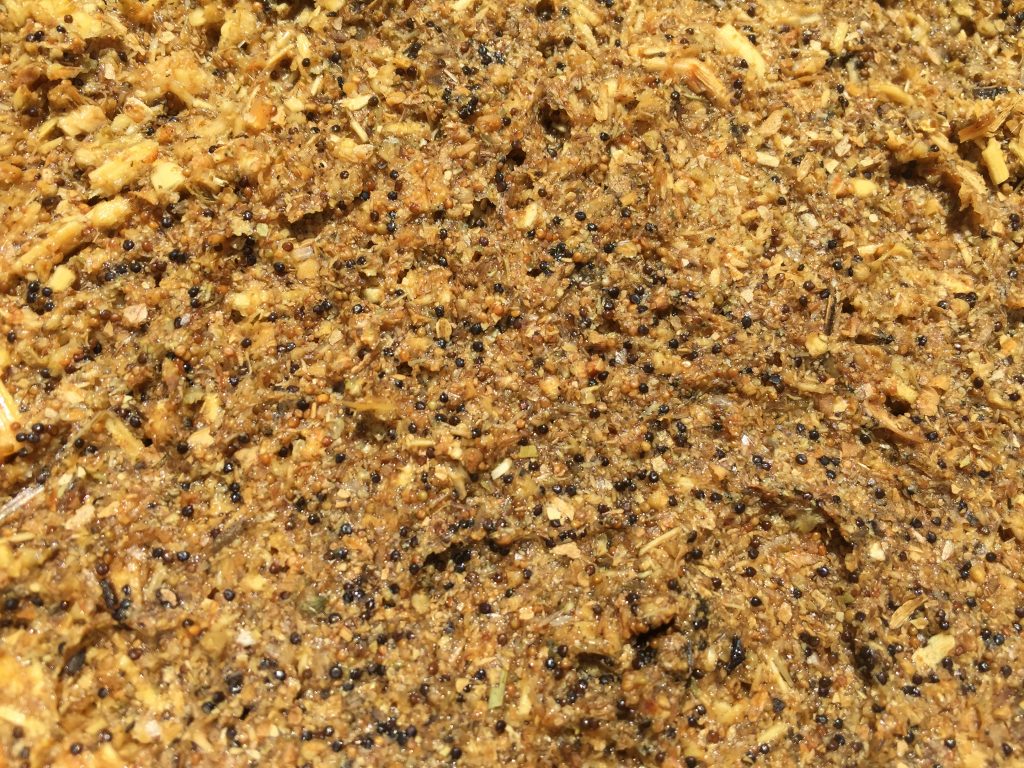

We weighed out 51 ounces each of dried, chopped madder roots and dried, chopped weld. We set them to soak in buckets of water at 10 am.

Even when the plant material was dry, the volume was significant. Once the dried plant material started to absorb water, I knew it would swell like crazy. So, we soaked it in 5 gallon buckets. Here’s a close up of the madder bucket:

The bucket sat all day and overnight. When working with madder, I like to extract the roots twice or even three times, and let the roots sit overnight each time. Then, I combine the extractions. In this case, I had time constraints, so I only extracted them twice.

After soaking the roots overnight, I extracted them once on Thursday morning. I had to split them between three pots. Due to being distracted, I let them overheat. There was not as much liquid in each pot as I might typically have, since the roots took up a lot of room. So, they heated faster than I anticipated and I just wasn’t watching closely enough. Other pots were also heating up in other locations in and around the apartment. Multi-tasking isn’t always a good idea.

Normally I am very careful not to let madder get hotter than 150 or 160 degrees F., and sometimes I keep it lower. Typically, I get the roots up to temperature, then maintain that temperature for an hour. I also add soda ash to get the pH up to 9 or so, and add some calcium carbonate (between a half teaspoon and a teaspoon per pot, depending on the size of the pot).

In this case all the pots got up to a boil. Frothy, red dye liquid and madder root particles got all over the stove. Yikes. So, I had to stop and clean that up.

Then the roots sat and cooled off for several hours. That evening, I strained out the roots and re-heated them. This time I watched the temperature carefully, and kept it around 150. The roots soaked in the second extraction overnight, and we used them for dyeing on Friday.

To prepare the linen, I had first washed all the cloth in a washing machine, and dried it in a dryer so it would be shrunk before we cut it. After the pieces were cut, I scoured them again with cationic scour from Earthues (which you can order from Long Ridge Farm in Westmoreland, NH) and soda ash. I follow Earthues’ recommendations of 5.5% WOG scour and 2% soda ash. I bring the bath up to 180 degrees F. hold for 30 minutes, remove the fiber promptly, and rinse.

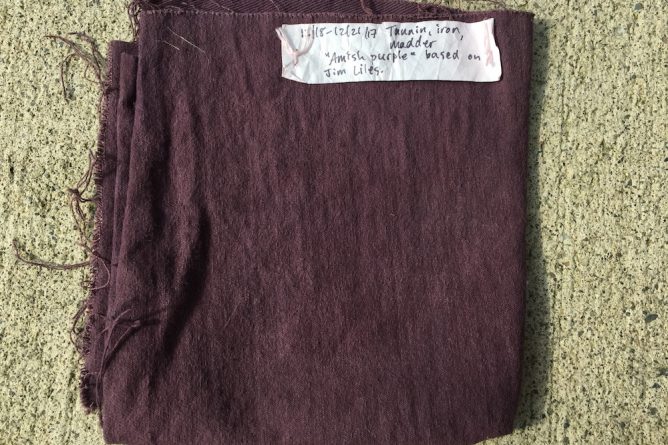

Then, I treated the linen pieces with a tannin solution. For the madder, I used a chestnut tannin at 5% WOG, heated to 180 degrees for an hour, and cooled overnight. Then I rinsed the cloth well. I hadn’t used this chestnut tannin before, and was kind of surprised at how foamy and soapy-looking it was.

It left the linen a pleasing shade of warm orange-tan.

Then I mordanted with aluminum acetate at 5% WOG, brought up to 180 degree, held for an hour, and cooled overnight. It’s a lot of steps just to get the cloth ready for dyeing.

The process for mordanting the silk was a little simpler. After washing the full length of cloth in the washing machine, I washed each piece again with the same laundry detergent, and rinsed well. The silk was mordanted with aluminum sulfate at 20% WOG. I was following Earthues’ mordanting rate, but I skipped the cream of tartar. Don’t ask me why. For mordanting, I brought the bath up to 180 degrees, held for an hour, and cooled overnight.

On Friday morning, Sarah Loomis from Smith came over around 8:30 and we got rolling with the dyepots. It had rained overnight and was raining first thing in the morning, but fortunately the rain stopped around 8. Here was the set-up. There was a lot going on:

I combined both of the madder extractions, then divided the bath in half. We were using one half to make cloth for the “red” part of the show, and the other half was going to be used to make “orange” in combination with weld.

I added more dissolved soda ash to get the pH back up to 9, and put the linen and silk pieces into the same dyepot:

I heated the bath up to 140 degrees, held it for an hour, and let the cloth steep and cool for the rest of the day and overnight. Here it was in the morning on Saturday the 13th:

I always do a delayed rinse, if I have time. I hung the cloth on the line to dry before washing it. In this photo, the madder “red” pieces are on the right:

Next up, the weld baths.