To re-cap, I had managed to transform linen yarns, grown and hand spun at Aker Fiber Farm in New Hampshire, from lovely shades of silvery- and golden-tan into more drab versions of same colors. This was deeply dissatisfying. But, if at first you don’t succeed… try, try again.

I thought about the factors that might have led to such disappointing color, and decided to change a few things the second time around. I was in a hurry at this point, because I was planning to deliver the yarns in just a couple days. So, I moved through some steps quicker than I normally do.

First, I made a fresh dyebath using only the very greenest of the walnut hulls that had been soaking outside. This involved finding the bucket that contained the hulls I had collected earliest in the fall, which was tucked under a table and very well protected from squirrels. It was a little bit of an excavation project. Again, I used 3 gallons of hulls to make the dyebath, but I only used the brightest green ones:

Second, I used fresh tap water to make the dyebath, not the liquid that the hulls had been soaking in. I heated the bath to about 180°F, maintained that temperature for two hours, then allowed it to cool and steep for a couple hours. I strained out the hulls while the liquid was still very warm, instead of giving it time to cool completely. I did not add any vinegar this time. The pH was 6.

Third, I re-mordanted the fibers with aluminum acetate at 5% WOG at 100° and let the yarns soak in the mordant solution for two hours. I rinsed the yarns before putting them into the dyebath. After about ten minutes in the dyebath, I decided that this situation really called for iron sulfate.

I’ve used tannin with iron on cellulose before. I have even written some blog posts about it. So I knew it would darken the color significantly. I had been hoping that with black walnut I could get a dark color without iron. But at this point in my story it was Thursday and I was planning to deliver the yarns on Saturday, so I figured I’d better go with something that I was certain would do the trick.

I dissolved 1 Tbsp. of iron sulfate in a tub containing 2 gallons of hot water. I pulled the skeins out of the dyebath and “worked” them briefly (meaning swishing them around in the solution to try to prevent blotches), wearing gloves all the while. The color shift to a dark brown was basically instantaneous. I returned the skeins to the dyebath without rinsing.

Then I continued to heat the skeins for an hour, and they cooled overnight in the dyebath.

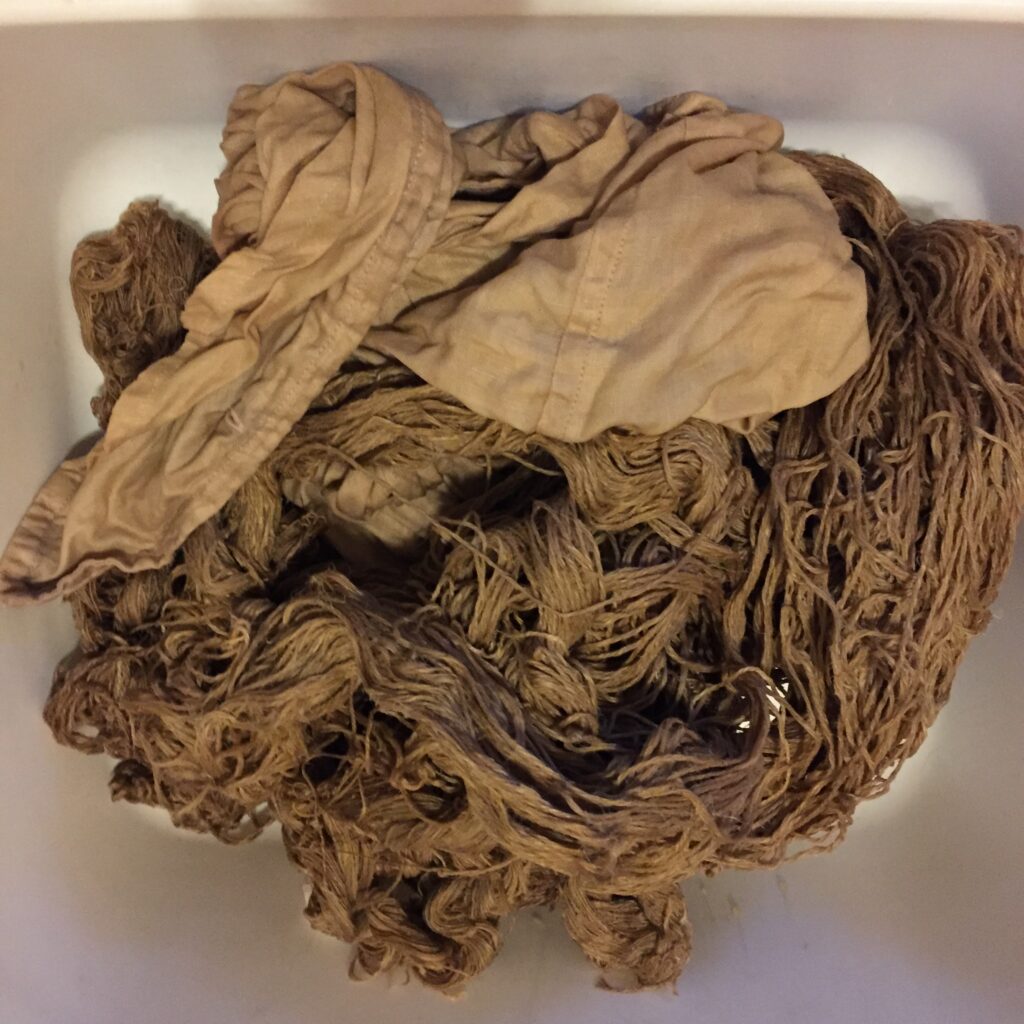

Once again, I let the the skeins drip and dry a little before rinsing. And, here they are all washed and dried:

You can see the yarns wound into balls by Locally Dressed here.

The color of the linen shirt actually grew on me as it dried, so I left it alone. Obtaining an unbleached-linen look on linen is a lot more satisfying when that wasn’t the original color!

I do believe that the greener and more resinous the hulls are, the richer the color you will get. However, I’m positive that it was the iron sulfate that ultimately created the dark color I was able to achieve on the linen yarns. I am currently taking the Maiwa class Natural Dyes: Alchemy Chemistry Craft, so in a few weeks I will be much better informed about the chemistry of the tannin-iron reaction!

I am a lot more cautious about using iron on wool. A fresh dyebath, with no tannin or mordant at all, yielded this medium brown on Western Massachusetts Fibershed white wool singles spun at Green Mountain Spinnery: