This is my 250th blog post. It feels momentous. As I anticipated this post, I tried to decide whether I should write something just about the momentousness of the occasion, or write a post that will help me catch up on the backlog of topics that I’ve been meaning to write about. I read back through some of my earliest posts to ponder the best course.

My very first blog post was about black walnuts, but it’s too early to be using those just yet. My second post was about weld. I recently used weld for my Smith College Botanic Garden project, so that gave me a “full circle” sort of feeling to mark the occasion. Weld it is. Me and weld, we go way back.

Ironically, for the Smith project I did not use my own weld. I have been growing it for years, and saving my own seed for years. However, for this project I didn’t want to blow my whole stash on one project. So, we ordered weld from Aurora Silk because they had a volume discount on 5 lbs., which is what we bought (and used).

I had to laugh at the description on their website: “Weld smells delicious, like honey, and bees love the flowers.” It is absolutely true that while the plant is blooming, bees love the flowers, and that the flowers smell amazing. Dried, it is another matter entirely. And this was the stinkiest weld I have ever smelled!

As with the madder that I wrote about in my last post, we set the weld to soak in a 5 gallon bucket on July 10th. We soaked 51 ounces of finely chopped weld. That’s just over 3lb. We didn’t have the wool gauze in hand yet, so I wasn’t using all the weld that week. Still, it was a lot by my standards. Here’s the bucket:

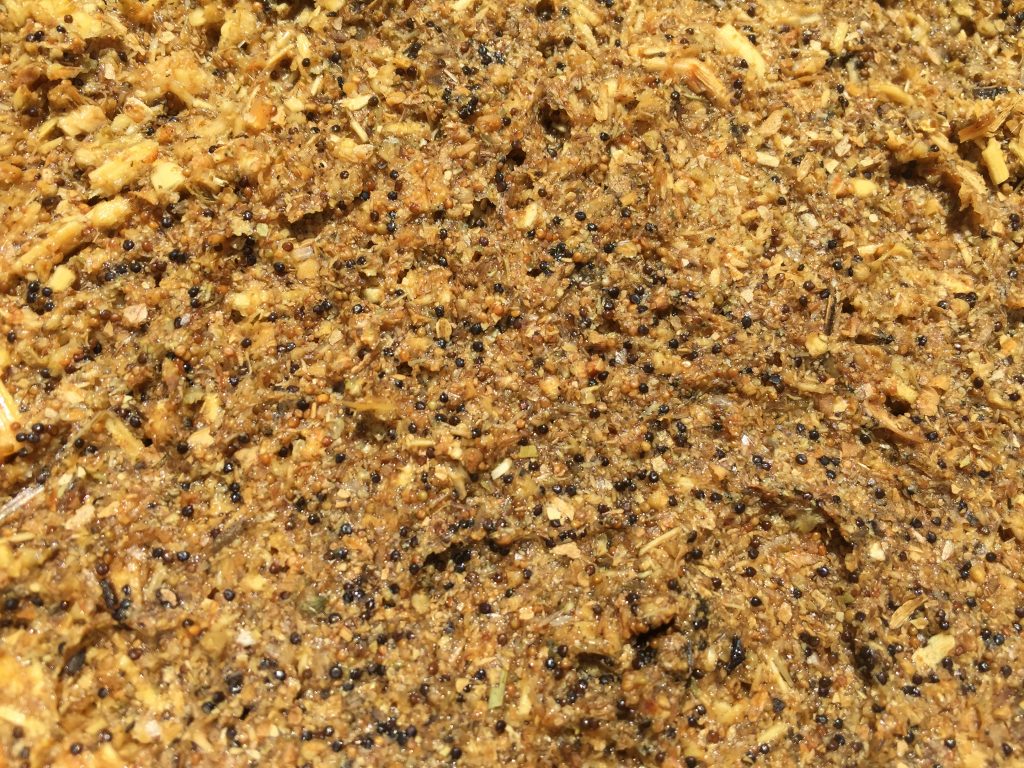

I took a closeup photo of the surface. I couldn’t believe how many seeds there were. Well, OK, I could believe it. Weld makes zillions of seeds. The seeds are the glistening black, tan, and yellow spherical dots on the surface, because they float:

Because I am who I am, I had to try germinating some of these seeds. They were easy to separate from the rest of the plant material:

Yes, some of them grew.

I now have Anatolian weld plants to add to my dye plant collection. I do not know whereabouts in the world my original plants came from, alas. It’s actually getting a little late in the season to put these in the ground, so we’ll see what happens.

The weld soaked overnight. As with the madder, I extracted it twice on Thursday. Again, I divided the plant material into two or three pots. Here’s the first extraction heating up on Thursday morning July 11th:

Here’s Sarah on Friday morning helping me to strain out the plant material from the second extraction:

I typically add chalk and soda ash to weld for maximum oomph, so that’s what I did. Even though weld makes fantastic yellows in its own right, this time I was using it to make two secondary colors, green and orange. For the orange, I combined half of the weld bath with half of the madder bath. I guess I took a photo of the linen on Friday afternoon, but not the silk for some reason:

FYI, I prepped the linen and the silk for the orange bath just the same way that I prepped them for madder, which I wrote about in my last post. The linen was scoured, treated with chestnut tannin, then mordanted with aluminum acetate. The silk was just washed and mordanted with aluminum sulfate.

For making green, I had decided to dye the linen and silk blue first in the woad vat that we ran on Wednesday July 10th. For many years I have had good success dyeing woolen yarns blue first, then mordanting and dyeing them with yellow to make green. I have had much less success with linen or cotton using this method. Catharine Ellis’ research convinced me that the best way to make deep greens on cellulose fibers and silk was to do the woad dyeing first. All of her blog posts are incredibly informative, but this is the one that shifted my thinking about making green.

So, I dyed the linen and silk pieces in the woad vat on Wednesday July 10th. To prepare the linen for the weld bath, I decided to use gallotannin from Earthues (bought from Long Ridge Farm) since it is a lighter tannin.

There must have been some metal contamination as the cloth sat overnight, because by the morning the liquid was dark and so was the cloth. On some of my dye pots, the handles are attached with rivets. I’m thinking that the rivets leaked iron or other metal into the tannin bath. At first I was dismayed.

Normally I just rinse cloth with water between each step of the preparation, but I used detergent to see if the gray color would come out of the cloth. This is the color of the liquid when I washed the fiber:

Fortunately, the cloth did lighten up:

I did not save the tannin baths to re-use them as I normally would:

After the tannin preparation, I used aluminum acetate to mordant the linen. I mordanted the silk with aluminum sulfate.

Here’s the weld bath with woad-dyed linen and silk on Friday afternoon. The bath heated up to 180 degrees, maintained for one hour, then steeped the rest of the day and overnight. The pH was 9:

Yes, the silk is yellow and annoying. The linen is lovely. Here they are on Saturday morning. This is the linen:

This is the silk:

Here they are drying on the line on Saturday morning:

Here are the 9-foot pieces from that week hanging on the line on Saturday afternoon once they were all rinsed. I ended up overdyeing the silk pieces in a later woad vat:

Unfortunately, even though that weld bath was rich and luscious, it was so stinky that I couldn’t keep it for long. I ran a couple exhaust baths on woolen yarns with my Summerfun campers the following week at the Common School, but then they voted to throw it out due to its foul smell. It was great while it lasted!