I love gardening. As someone who doesn’t own property, I have always been grateful for access to land to cultivate a garden, whether it was a town community garden plot or space on a farm owned or managed by a generous neighbor. There’s nothing quite as grounding or satisfying as getting my hands in the dirt and tending plants.

However, gardening can be full of frustration and disappointment. It can be exhausting. One’s labors can be many and one’s successes few.

Gardening dye plants comes with a particular irony for me. You can’t eat them. They are not, strictly speaking, necessary. One can certainly live without dye plants. Why go to all that trouble?

I started writing this post in the summer of 2020. We had a dry spring. We had a dry summer. As of May 2020 our part of the state was under “significant” drought conditions, which persisted through the fall. We were lucky never to get to the “critical” level that other parts of the state faced. You can check out the map of drought conditions in Massachusetts here, with updates posted throughout the summer and fall. I spent a ridiculous number of hours hauling gallons of water via car, which comes with a fossil fuel burden, trying to keep a couple beds of woad alive. I gave up entirely on the bed of flax I planted in April.

Honestly, why bother?

I know why I love making dyes with plants. Color is beautiful and beauty makes me happy. To be able to participate in this process of beauty-making helps me feel connected to, and part of, the many incredible forms of life on this planet. Creating color feels magical and meaningful. It is mind-boggling and humbling that plants can give these colors to us, over and above all the other gifts that plants bestow. Medicine, food, fragrance…. Oxygen alone would be enough! I am deeply grateful to plants for all their lessons and awe-inspiring power. “Hey, need some color to brighten your day? Let me help you with that.”

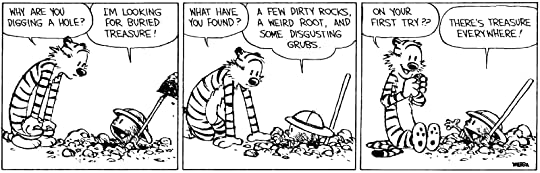

But sometimes I look at all the abundant color that grows freely, of its own accord, with no effort expended on my part, in the fields and roadsides all around me, and wonder why I work so hard to maintain a dye plant garden. July and August (when I first started writing this post) are especially good times to reflect upon the abundance and take stock. There’s treasure everywhere (to quote a beloved line from Calvin and Hobbes).

It’s the middle of winter now. Gardeners are planning gardens and ordering seeds, or feeling glad for seeds saved. What to devote garden space to, and what to gather by the wayside?

Here are a few of the most prolific dye plants in my neighborhood, photographed in June, July, and August of 2020. I will save a discussion of the use and implication of terms such as invasive, noxious, and opportunistic for another day. Hopefully “introduced” or “naturalized” are accurate enough for now.

Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota) is an introduced species from Europe that can be found everywhere. It makes a lovely cool, clear yellow. It readily fills in marginal spaces along the side of the road, next to railroad tracks, and under power and utility lines.

It also fills in fields and open places. It is so prolific that I usually use just the flowers for dyeing, but I suspect the foliage gives similar colors. Also, it smells delicious when the dye bath is heating up!

Next up, tansy (Tanacetum vulgare). It is also introduced from Europe. It is also quite aggressive. It is another source of yellow, albeit stinkier. It’s more on the gold side of yellow, a bit more brassy or brown than Queen Anne’s lace.

Purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) is yet another introduced species from Europe. It is especially known (and lamented) for displacing native wetland plants in New England, but can also be found in drier habitats along the side of the road or underneath power lines. Whatever else one may wish to say about purple loosestrife, it is stunningly beautiful and makes bees very happy.

Purple loosestrife can make a variety of colors ranging from tan to olive green to gray, with the use of iron. I have even read a recipe for making black, but the amount of iron and heat called for seem overly harsh for wool. I feel like it has a lot of potential as a tannin source, and I haven’t explored it nearly enough.

Also visible above is jewelweed (Impatiens capensis) which is a native species here in New England. I have never used it for dyeing. I have heard from other dyers that it makes a rich yellow or gold. Personally, if I’m gathering rather than cultivating, I tend to stick with dye plants that are generally agreed to be *too* abundant. If I’m going to use a native species, I feel that it, too, ought to be unquestionably abundant. While jewelweed is not at risk or endangered here in Massachusetts, I don’t tend to find it in wide swaths, so thus far I have left it alone.

A native plant here in New England that I feel totally fine using is goldenrod. There are several species, and I’m sorry to say that I can’t identify them all, so maybe I shouldn’t be so cavalier. The type I’ve used is Solidago canadensis, I believe, though I am not positive that I can tell it apart from Solidago odora or sweet goldenrod. Yes, it makes yellow. A cheery, intense yellow. I think it’s the most vivid when you pick the flowering tops just before they are starting to bloom, when the buds are still pretty tight and the overall color is a neon greenish-yellow. In this photo it is a modest presence amidst a collection of other plants, but you can often see it filling whole fields around here.

For now, I think I’ll wrap things up with black walnut (Juglans nigra). The green hulls from the nuts of these tall, lovely trees are a rich source of brown. Last year was actually not an abundant year for black walnuts. These were some early drops in August, and after that I didn’t find many mature nuts. Maybe it was the drought or maybe just not a mast year for black walnuts.

In a more abundant year, I can easily collect a five gallon bucket full from underneath just one tree.

To get the most intense color from black walnut hulls, you have to pick them up promptly and use them while the hulls are still green. They also smell wonderfully fragrant at this stage. If they sit on the ground too long, they start to get soft and black, and teeny little maggots start to grow. I believe that these are either walnut husk flies or walnut husk maggots, but I need to read up more about them. I find them squirmy and off-putting, but I’m sure they have their own lives to live and jobs to do on this earth, so I feel kind of bad boiling them to death.

As Calvin gleefully notes above, one of the treasures that are everywhere are disgusting grubs!