After three extractions and a lot of soaking in between, my madder and lichen baths are ready to go. I’m sticking with Flavoparmelia caperata for the ID on the bark-growing foliose lichen, though I’m sure I could be wrong.

For each dyebath, I combined all three extractions. Next for some tinkering.

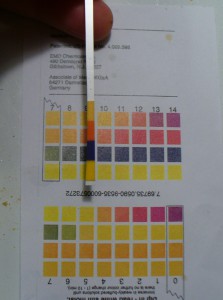

Here are the color and pH of the madder bath before I did anything to it. Brown.

I would call that pH6 which is acidic, not where I want it to be to develop good reds. So, first I added more calcium carbonate (there was already one teaspoon in the roots as I extracted them). This did not produce much of a pH shift (see below). I’d still call that 6, though I don’t know what’s up with that bottom square. It’s not supposed to be so orange. Happily, the color darkened and shifted a little from brown to red.

I wanted to get the pH up a little, so I added 1/2 teaspoon dissolved soda ash at first, which got it up to pH 8 (photo on the left below). The dyepot contains about 2 gallons of liquid. I did not weigh my modifiers or figure out the percent on the weight of the dyestuff this time around (I extracted 8 ounces of roots). After another half teaspoon of dissolved soda ash, the pH was 9, which I was happy with (photo on right).

I wanted to get the pH up a little, so I added 1/2 teaspoon dissolved soda ash at first, which got it up to pH 8 (photo on the left below). The dyepot contains about 2 gallons of liquid. I did not weigh my modifiers or figure out the percent on the weight of the dyestuff this time around (I extracted 8 ounces of roots). After another half teaspoon of dissolved soda ash, the pH was 9, which I was happy with (photo on right).

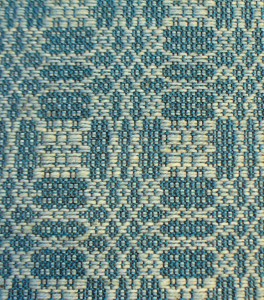

Since I’m dyeing linen, I’m not worried about making it too alkaline. I introduced a 2 ounce skein of 20/2 linen half bleach, which I had mordanted with alum acetate back in December, and re-mordanted yesterday for good measure. After 30 minutes heating, the color was promising:

Here is what it looked like once I got up to my target, and maximum, temperature of 160 degrees (over 160 you’ll get brown rather than red tones):

Here is what it looked like once I got up to my target, and maximum, temperature of 160 degrees (over 160 you’ll get brown rather than red tones):

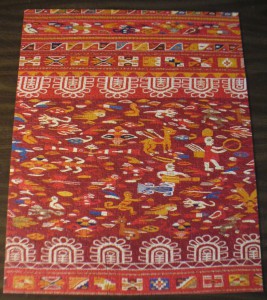

I am very satisfied with this so far. My quest to create rich color on linen yarns seems to be advancing, though I shouldn’t speak too soon. The color is always lighter once it is dried and rinsed. I held the temp between 150 and 160 for an hour (and actually had to shut off the heat for a while to keep it from getting too hot). Next, the skein will sit and soak all day and overnight in the dyebath, and then it’ll drip dry before I rinse it. I find that delaying the rinse helps with fastness. So, that’s the status of the madder bath. As the week progresses, I expect to re-use the bath repeatedly and get a lot of pink, salmon, apricot, and so on until it’s exhausted.

I am very satisfied with this so far. My quest to create rich color on linen yarns seems to be advancing, though I shouldn’t speak too soon. The color is always lighter once it is dried and rinsed. I held the temp between 150 and 160 for an hour (and actually had to shut off the heat for a while to keep it from getting too hot). Next, the skein will sit and soak all day and overnight in the dyebath, and then it’ll drip dry before I rinse it. I find that delaying the rinse helps with fastness. So, that’s the status of the madder bath. As the week progresses, I expect to re-use the bath repeatedly and get a lot of pink, salmon, apricot, and so on until it’s exhausted.

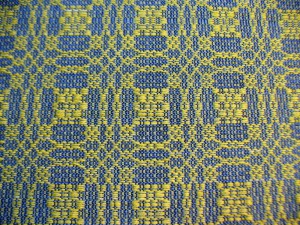

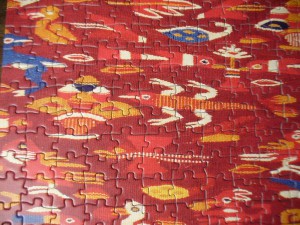

The Flavoparmelia experiment is less exciting, but at least now I know not to bother with it again, so that’s useful information anyway. Here’s the initial color of the dyebath with all three extractions combined (I started with 5.4 ounces of lichens including a lot of bark).

The pH was a bit weird. I didn’t take a photo (by now you’re probably tired of photos of pH strips). It looked like 6 at first, but as the liquid wicked up it shifted to 5. The initial color of the skein was light and not promising.

The pH was a bit weird. I didn’t take a photo (by now you’re probably tired of photos of pH strips). It looked like 6 at first, but as the liquid wicked up it shifted to 5. The initial color of the skein was light and not promising.

Just for the heck of it I decided to see if the color was pH sensitive (since I already had the soda ash out anyway…). I put some of the hot dyebath liquid in a jar and added 1/4 teaspoon of soda ash. It darkened, so I decided to add this solution to the dyebath (I took out the skein first). Since this dyebath contains less liquid than the madder pot, about one gallon rather than two, even such a little soda ash had a noticeable effect on the pH, which went up to 8.

Just for the heck of it I decided to see if the color was pH sensitive (since I already had the soda ash out anyway…). I put some of the hot dyebath liquid in a jar and added 1/4 teaspoon of soda ash. It darkened, so I decided to add this solution to the dyebath (I took out the skein first). Since this dyebath contains less liquid than the madder pot, about one gallon rather than two, even such a little soda ash had a noticeable effect on the pH, which went up to 8.

OK, I guess there isn’t a big difference between these two photos. On the left is the yarn halfway through heating it, and on the right is how it looks after sitting and soaking for eight hours. I do not plan to exhaust this bath.