In anticipation of Valentine’s Day, I’ve been weaving bookmarks with heart motifs in huck lace. I really like them. They have a sweet, old-fashioned feeling.

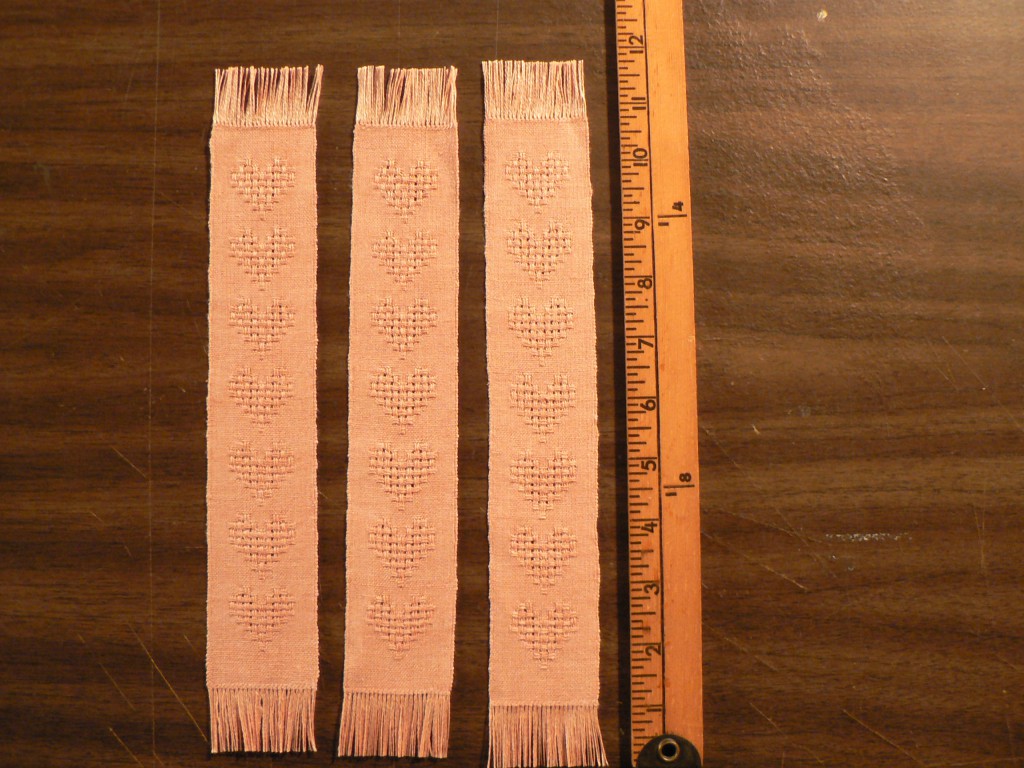

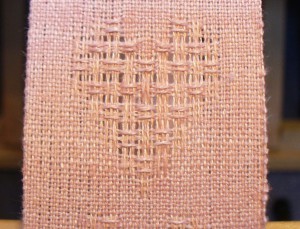

Here are three next to a yardstick to show length. Click on the photo to see more detail. The weave structure of huck lace creates floats that pass over five threads, and these reflect light more than the plain weave background. The reflectivity or sheen helps differentiate the pattern.

I’m using 40/2 linen that I dyed with madder root last summer. The warp and weft are slightly different colors, and came from two successive dyebaths. The madder roots were leftover from an excellent, inspiring workshop last summer with Joan Morris at Long Ridge Farm (unfortunately a “what I did this summer” post that never got written). By the time I dyed these linen skeins, the roots had been extracted twice already, hence the light colors.

The warp is slightly more salmon colored, toward the orange side of red. The weft is lighter pink, more toward the blue side of red. To my eye the colors and values blend smoothly; except along the hemstitching, I don’t see the difference. I was surprised to see in this photo, though, that the camera picked up the differences in color.

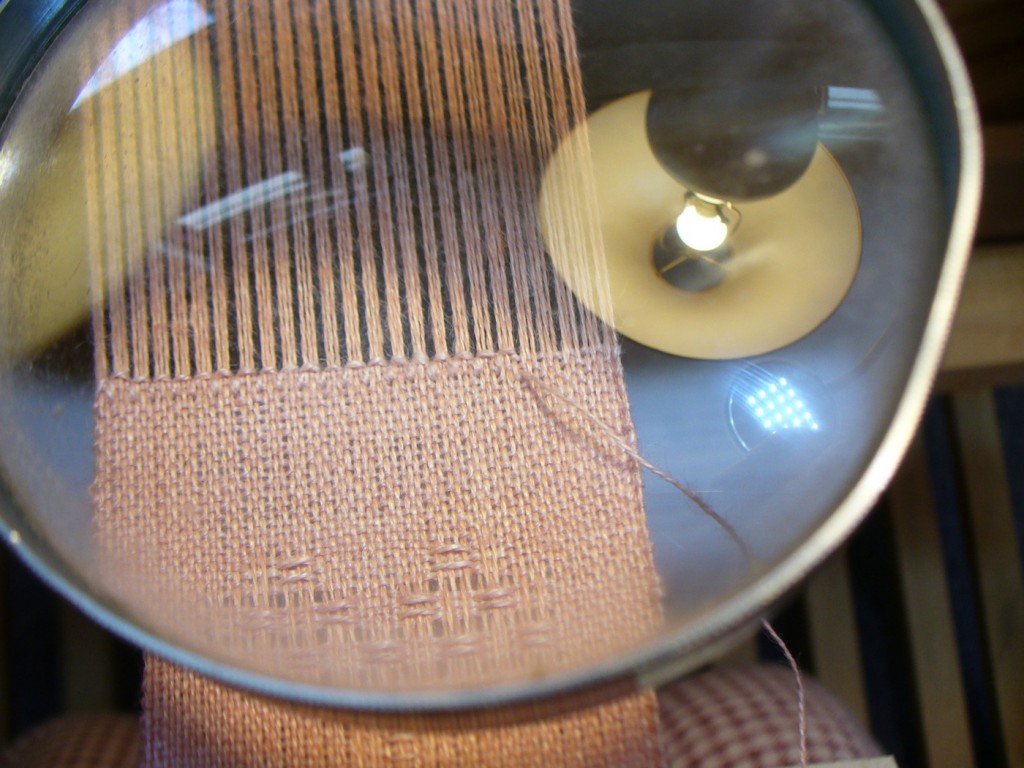

The threads going across are the weft, and the ones going up and down are the warp. The sett is 36 epi (ends per inch), sleyed 3 per dent in a 12 dent reed. The bookmarks are two inches wide in the reed, an inch and three quarters after washing and ironing, and range from 10 and a half to 11 inches long including the fringe. I have woven 20 at this point.

Mostly these bookmarks have been fun and satisfying to weave. The only difficulty I’ve encountered is the hemstitching. The yarn untwists as I work and starts to disintegrate. Re-twisting and wetting it helps a little, but it’s still a tricky business, even though the bookmarks are only 2 inches wide. By the time I get to needle-weaving in the ends, there’s not much left to work with. That’s problem number one.

Problem number two is that, at 36 epi, it is hard to see what I’m doing. So, I’ve been using a magnifying glass to help. It would be more efficient to have one on a stand so I could keep both hands free, but I do OK with a handheld one. Sometimes the hemstitching goes smoothly. I feel skillful. Other times there’s fraying and lumps and wispyness. I feel inept.

Here’s where Chuang Tzu comes in. If you’ve heard of Taoism, you’ve heard the sayings of Chuang Tzu: he’s the guy who inspired it all 2000+ years ago.

While I was enjoying a happy hemstitching experience and contemplating its pleasures, a story from Chuang Tzu came to mind. It’s about a butcher, or cook, who never needs to sharpen his knife. I’ve been a vegetarian for about 30 years, but I still like this story. Here’s a little excerpt from the Burton Watson translation. Cook Ting is cutting up an ox for Lord Wen-hui, who marvels at his skillfulness, and Cook Ting says …

“I’ve had this knife for nineteen years and I’ve cut up thousands of oxen with it, and yet the blade is as good as though it had just come from the grindstone. There are spaces between the joints, and the blade of the knife has really no thickness. If you insert what has no thickness into such spaces, then there’s plenty of room–more than enough for the blade to play about in.”

This is how it is with hemstitching. If you slip the needle through the spaces between the threads, it all goes smoothly. There is less abrasion on the thread, less interference with the structure of the cloth, and nothing wears out. I decided I needed a needle with less thickness. Voilá, easier hemstitching! And the magnifying glass helps.

Cook Ting describes how he feels when he has successfully worked through a “complicated situation” …

“I stand there holding the knife and looking all around me, completely satisfied and reluctant to move on, and then I wipe off the knife and put it away.”

One more bookmark completed. I feel satisfied, then I advance the warp. The Tao of hemstitching.