Part Five: Picking up Fallen Lichen in the Non-Snowy Woods

Right after the big storm in October, we had a spell of very warm weather and all the snow melted at the beginning of November. However, the broken trees and branches still lay everywhere. Lichen and salvage botany were very much still on my mind. Karen Diadick Casselman wrote in Lichen Dyes that in the woods behind her house, several species of lichen dropped daily to the ground, which provided an almost unlimited supply, should she choose to use them. (She went on to say that she focuses on studying lichens rather than on dyeing in volume.) I wondered how much lichen could be gathered if I picked up only what had fallen on the trail, road, or sidewalk as I went on my walks, and only what was most abundant. Well, in one week of walking almost every day, I had 4 cups of this lovely stuff (including quite a lot of bark, to which it was attached):

To be honest, I’m not positive it was all the same species, but visually all the little pieces looked very similar. I could sure collect a lot of it, but what exactly was it, and was it useful for dyeing?

Positively identifying it has been an on-going process. Today I completed the most recent step, having acquired a container of lye from my mom, whom I visited yesterday. Thanks, Mummy!

Earlier in the winter, I had gone through the dichotomous key for “foliose lichens that are not umbilicate, jelly-like, or yellow” in Lichens of North America. With a pretty good degree of confidence I continued on to the Parmelia key. The most likely candidates were Flavoparmelia caperata (a.k.a. Pseudoparmelia caperata, the Common Greenshield lichen), Flavopunctelia soredica, or Flavopunctelia flaventior. The time had come for chemical testing.

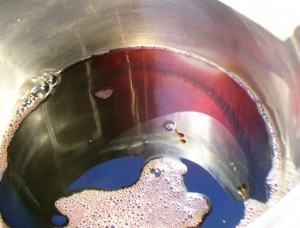

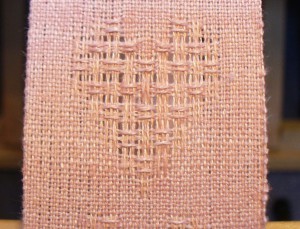

I hoped that using just bleach for the C test (short for calcium hypochlorite), I could tell the difference between F. caperata and F. soredica or F. flaventior. Here’s why. Both of the latter are supposed to react C+ red when spot tested on the medulla. That means when you scrape off the top layer (cortex) and expose the white layer underneath (medulla), then apply a dab of bleach to the white area, it will turn red. It didn’t. Here’s a photo comparing the foliose lichen in question with an umbilicate lichen that definitely did react C+ red.

The umbilicate is in the lower part of the photo, and shows a very bright red-orange reaction. The foliose lichen above shows very little color change. Depending on how dramatic the reaction is supposed to be, you could call it yellow, or you could call it nothing. On the medulla of the foliose lichen, there was more of a reaction (the spot on the upper right which is a little bit darker yellow), but it’s definitely not red.

Having ruled out F. soredica or F. flaventior, I was pretty happy to say that my abundant foliose lichen was Flavoparmelia caperata. But I didn’t actually prove what is was, only what is wasn’t. Enter the lye, which lets you do the K and KC tests (K stands for the potassium in potassium hydroxide)

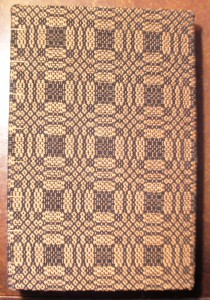

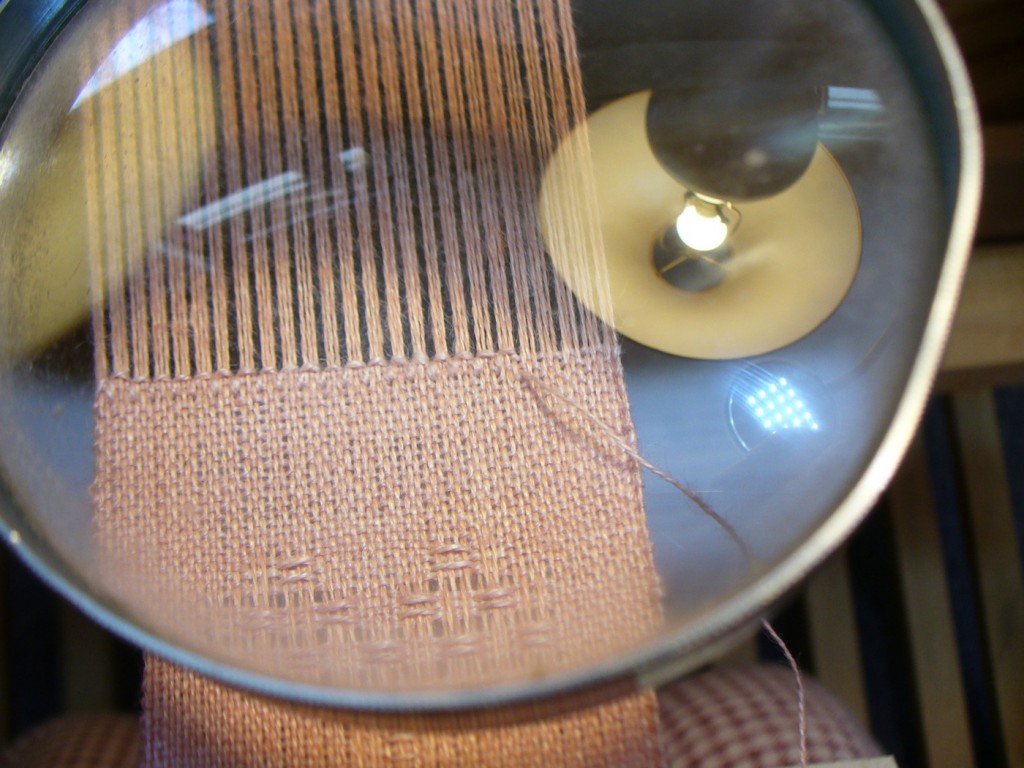

F. caperata is supposed to be K- on the cortex and medulla, KC + gold on the cortex, and KC+ pink on the medulla. Here’s what my results this morning looked like. The first photo shows a piece of the lichen with the medulla exposed (the white area):

The photo above shows the K- reaction on the cortex, and the one below shows K- on both the medulla and cortex. It’s slightly brighter green where I dabbed on the lye solution because it’s wet.

The photo above shows the K- reaction on the cortex, and the one below shows K- on both the medulla and cortex. It’s slightly brighter green where I dabbed on the lye solution because it’s wet.

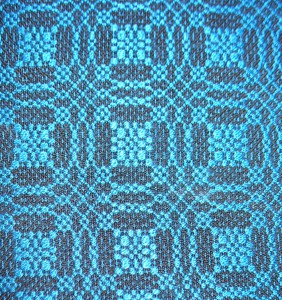

The photo below shows the KC+ reaction on both the cortex and medulla. (KC means you apply a dab of lye solution, then a dab of bleach on the same spot.) However, I would not call the color on the medulla “pink,” exactly. It’s redder than the gold on the cortex, but it’s more orange, I’d say.

The photo below shows the KC+ reaction on both the cortex and medulla. (KC means you apply a dab of lye solution, then a dab of bleach on the same spot.) However, I would not call the color on the medulla “pink,” exactly. It’s redder than the gold on the cortex, but it’s more orange, I’d say.

On the other hand, my “red” reaction on the umbilicate was sort of orange, too. So, there you have it. Probably my abundant foliose lichen is Flavoparmelia caperata. It does not appear to be an interesting source of dye, unfortunately. I may go ahead and try it anyway. I’ll let you know.